CAE simulations. The art of the possible.

The recent article was about CAE software development. This time, let’s take a look at CAE projects. Specifically, what factors contribute to making CAE projects successful? In the company I work for, in 15 years, we have delivered hundreds of CAE projects to industrial companies (most of them in the turbomachinery field). Some projects were highly successful, while others were not. In this article, I would like to share a few thoughts and lessons learned about project-success patterns and engineering productivity in general.

The Game

In engineering, we don’t simulate reality. We merely simulate our understanding of reality with currently available resources. In other words, the game we play here is about turning our knowledge and effort (and talent) into the best possible results. CAE projects, like software, are never really finished. They only have their versions. At any point, you can make them better. When chasing accuracy, the effort grows exponentially, so it’s smart to recognize the point when the results are good enough. Having clear, measurable goals is critical to prevent infinite drift, resource waste, and disappointment. Well-defined goals help to navigate, focus, and prioritize. The game we play is all about goals and their feasibility with the available knowledge and effort.

Theory vs. Practice

What makes CAE both fascinating and frustrating at the same time is the weak connection between theory and practical results. In CAE, everything is easier said than done. The simulation theory is rooted in physics, mathematics, numerical methods, and software engineering. In practice, it’s constrained by: limited computational resources, incomplete physical & material data, boundary condition assumptions, and numerical discretization (you go from continuous to discrete). CAE is not a calculator. There is nothing like a perfect simulation. We can only have a good approximation (when we are lucky enough). In CAE, we’re putting continuous functions into discrete values via generalized physical models with multiple tradeoffs and a huge amount of uncertainty. We have a huge parametric space. A problem of a highly dynamic system with hundreds of parameters and almost infinite variations.

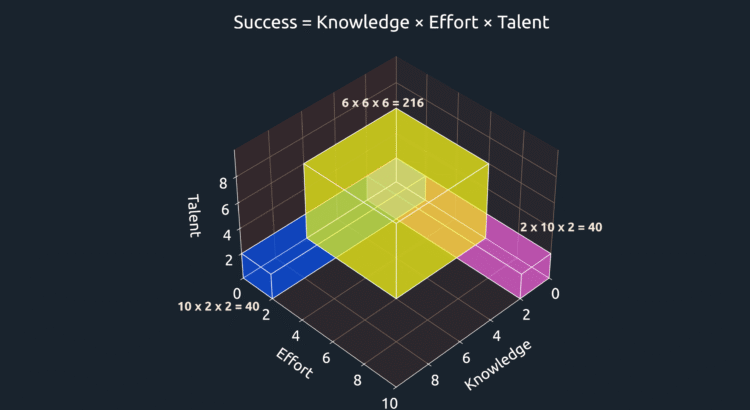

CAE Projects Success = Knowledge vs. Effort

If theory and practice define the playing field, then our knowledge and effort are the keys to success. Every CAE project’s success is a result of these two dimensions. Knowledge represents our understanding of physics, mathematics, and tools, while effort reflects the resources, budget, and time we are willing or able to invest. Success can be imagined as the area in a two-dimensional plot of knowledge versus effort. Small knowledge with little effort yields nothing. High knowledge without sufficient effort produces poor results. Excessive effort applied without knowledge simply burns time and money. True project success happens when knowledge and effort are balanced to boost the success area.

Knowledge itself is not a single thing. It is a combination of experience, skills, and theory. Theory provides the framework: the equations, physical laws, and assumptions behind our models. Skills allow us to use the tools effectively: to create geometries, generate meshes, run solvers, and automate workflows. Experience connects it all, teaching us what matters and what doesn’t. This is where engineering intuition comes from: the hard-earned ability to make judgments in complex situations.

Effort is more tangible, but equally critical. It comes down to the resources we can access, the budget we have, and the time we’re willing to invest. This is where project management collides with engineering reality. CAE projects are less about reaching perfection and more about operating within the circumstances available.

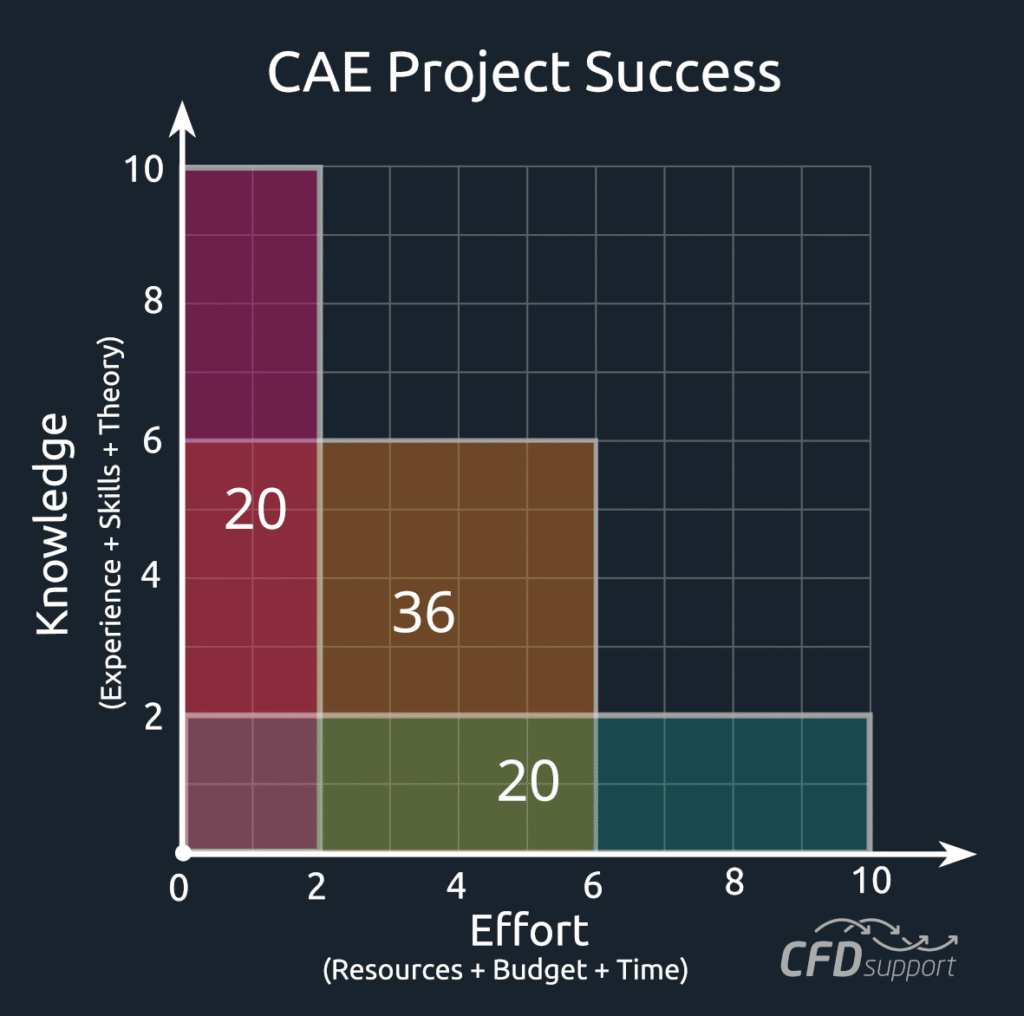

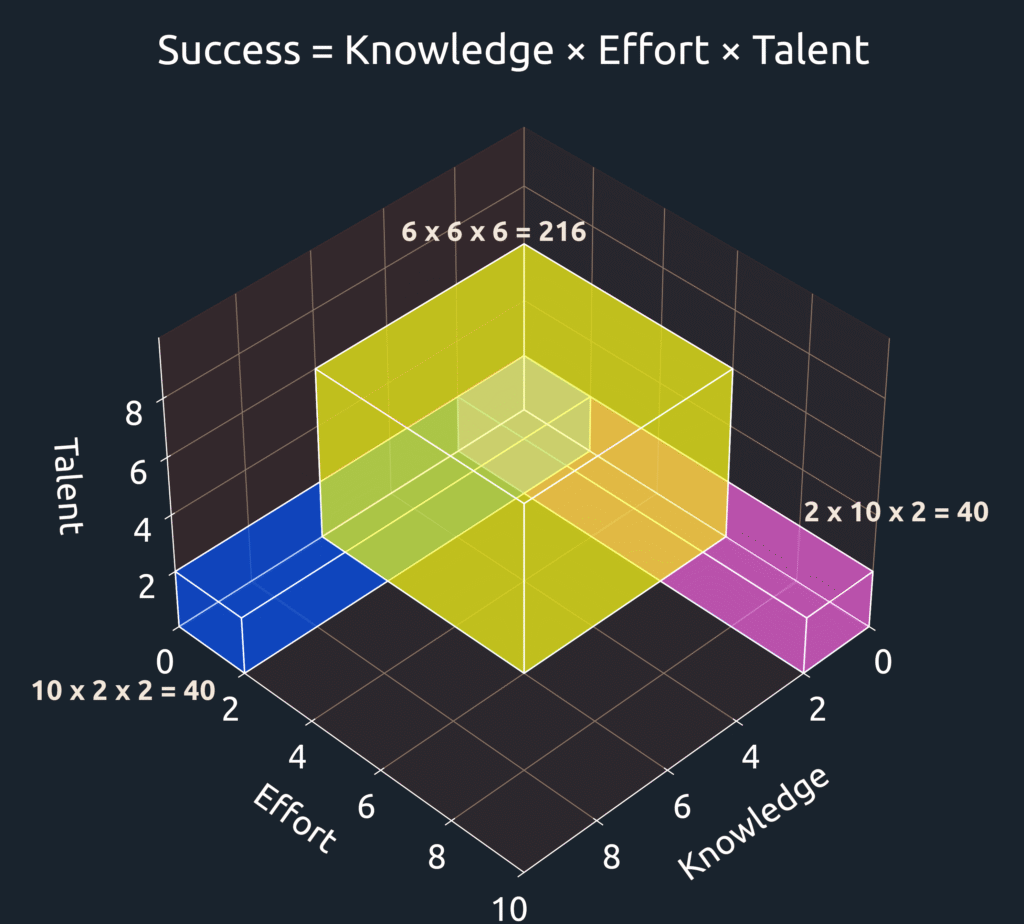

Scaling factor: Talent

If knowledge and effort define the plane of CAE project success, then talent acts as the scaling factor that lifts it into a third dimension. In this sense, talent is what turns a two-dimensional area into a three-dimensional volume. It doesn’t replace knowledge or effort but amplifies both.

Talent is difficult to quantify, but we’re seeing its effects every day. It’s a winner mentality. It’s personal productivity. It’s creativity. It’s the ability to recognize patterns in noisy data. It’s an instinct to point to which simplifications are still safe. It is the ability to spot potential problems early. It is the ability to navigate complexity without fear.

In a 3D plot of knowledge versus effort versus talent, project success becomes the volume enclosed. With high knowledge and effort, talent multiplies the outcome. This is why talent often acts as the hidden multiplier in CAE projects. In discussions with clients, I very often say (defending our rather small engineering team) that CAE engineering isn’t about quantity but about quality. And I never forget to mention my favorite parallel between CAE engineering and the assembly line …

As a result, two teams with the same tools, budget, and deadlines can deliver dramatically different outcomes depending on who is doing the work. In an environment where resources and time are finite, talent turns the CAE projects into the art of the possible. This is where CAE stops being a purely technical exercise and becomes something closer to a craft. It is less about mechanical work, and more about knowing how to navigate complexity within real-world constraints.

Conclusion

This is why the human factor is so critical in CAE. People often get lost in comparing software capabilities, chasing solver features and performance benchmarks, while overlooking the far more decisive element: the engineers who use them. Software produces data. Humans produce results. We routinely overestimate what our codes can do, while underestimating the role of experience, intuition, and creativity in making sense of it all.

At its core, CAE is an attempt to impose order on complexity. We try to bound chaos with grids and solvers in a finite computational domain, but having an infinite parametric space.

And that is the essence of CAE. It’s not about finding an absolute truth, because such a thing doesn’t exist in engineering. It’s about finding what matters. Constrained by theory, unlocked by creativity, and realized through tools, our job as engineers is to move decisively through that landscape—choosing trade-offs, setting priorities, and recognizing when “good enough” truly is good enough.

In the end, CAE projects are not the hunt for perfection. They are the art of the possible. ∎